Gershon Baskin, who has studied regional water problems for 20 years, claims that the Israeli drought for Jordan it is a survival issue where Jordan might lose half its crops in the east Jordan valley, which may be destabilising for the Jordanian regime

THE WORST drought in 50 years has led Israel to cut the supply of desperately needed water to Jordan, in a move likely to provoke a crisis in relations between the two countries.The failure of the winter rains – only 40 per cent of normal in Israel – will have a devastating impact on Jordan, which suffered a severe water shortage last year. In Amman, the Jordanian capital, householders found that when they turned on their taps they received only a trickle of grey liquid.

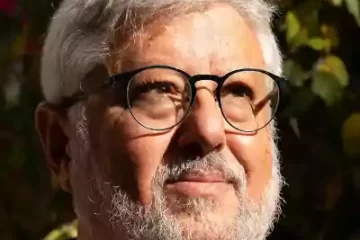

“It is very, very serious,” says Gershon Baskin, director of the Israel/Palestine Centre for Research and Information in Jerusalem. “By summer people in Amman may be getting only one or two days’ water a week. It is destabilising for the regime.”

Israel is pledged by treaty to supply Jordan with 45 million cubic metres of water annually, but has told the Jordanian government that it can only send 40 per cent of this. Israeli farmers have already had their supply cut by a quarter. The hills east of Jerusalem, usually carpeted with grass and wildflowers at this time of year, are as barren as in high summer. The government is expected to declare an official drought in April.

In Jordan the situation is much worse. Its own water resources are limited. In the east Jordan valley, the centre of Jordanian agriculture, one of the main canals has grass growing along its bottom. Last year the filtration plants at the Amman reservoirs stopped working, leading to toxic water flowing into the system.

Mr Baskin, who has studied regional water problems for 20 years, says: “For Israel it is an economic issue; for Jordan it is a survival issue.” He says that Jordan might lose half its crops in the east Jordan valley.

Jordan rejected outright the Israeli proposal at the weekend to cut the water supply. Israeli officials are concerned that the affair may provoke a crisis in relations, especially as the newly crowned King Abdullah will need to show that he can deal with the shortage.

In Israel the government gave the go-ahead earlier in this month for preliminary studies for a desalination plant. Experts argue, however, that the problem could be solved by cutting the subsidies to Israeli agriculture, which takes 60 per cent of the water in Israel but produces only2 per cent of the gross domestic product.

Countries in the Middle East have long quarrelled about water. Syria is vulnerable to Turkey damming the waters of the upper Euphrates for irrigation and agricultural schemes. Iraq is also dependent on the waters of the Euphrates, which can be dammed by Syria, and the Tigris, which comes from eastern Turkey.

But Jordan is the most vulnerable country in the region, with few water resources of its own. The oasis at El Azraq, east of Amman, once full of water fowl, is now largely dried mud. In order to cope with the water crisis Jordan has been draining its aquifers at an unsustainable rate.

Such water resources that it does have are at the upper end of the Jordan valley, where the Jordan river and the Yarmouk flow into the Sea of Galilee. Under the 1994 peace treaty between Israel and Jordan the country was to receive extra water from Israel. It is this which is now being cut.

Last year, the first full year when the plan was in operation, Israel met its obligations. But nobody expected such a serious drought this year, and there are no provisions in the treaty about what to do if a water shortage affected the whole region.

As with Israel, most of the water in Jordan is used in agriculture, which consumes 68 per cent of the total supply, while domestic use is only 28 per cent. On other hand, Amman, with a third of the Jordanian population, is expanding fast and using ever more water.

Originally Published at: http://goo.gl/3iRUqS